|

|

TODAY.AZ / Weird / Interesting

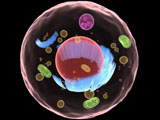

New genetic technique converts skin cells into brain cells

14 June 2011 [12:40] - TODAY.AZ

The new technique avoids many of the ethical dilemmas that stem cell research has faced.

The new technique avoids many of the ethical dilemmas that stem cell research has faced.For the first time, a research group at Lund University in Sweden has succeeded in creating specific types of nerve cells from human skin. By reprogramming connective tissue cells, called fibroblasts, directly into nerve cells, a new field has been opened up with the potential to take research on cell transplants to the next level. The discovery represents a fundamental change in the view of the function and capacity of mature cells. By taking mature cells as their starting point instead of stem cells, the Lund researchers also avoid the ethical issues linked to research on embryonic stem cells.

Head of the research group Malin Parmar was surprised at how receptive the fibroblasts were to new instructions.

"We didn't really believe this would work, to begin with it was mostly just an interesting experiment to try. However, we soon saw that the cells were surprisingly receptive to instructions." The study, which was published in the latest issue of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, also shows that the skin cells can be directed to become certain types of nerve cells.

In experiments where a further two genes were activated, the researchers have been able to produce dopamine brain cells, the type of cell which dies in Parkinson's disease. The research findings are therefore an important step towards the goal of producing nerve cells for transplant which originate from the patients themselves. The cells could also be used as disease models in research on various neurodegenerative diseases.

Unlike older reprogramming methods, where skin cells are turned into pluripotent stem cells, known as IPS cells, direct reprogramming means that the skin cells do not pass through the stem cell stage when they are converted into nerve cells. Skipping the stem cell stage probably eliminates the risk of tumours forming when the cells are transplanted. Stem cell research has long been hampered by the propensity of certain stem cells to continue to divide and form tumours after being transplanted.

Before the direct conversion technique can be used in clinical practice, more research is needed on how the new nerve cells survive and function in the brain. The vision for the future is that doctors will be able to produce the brain cells that a patient needs from a simple skin or hair sample. In addition, it is presumed that specifically designed cells originating from the patient would be accepted better by the body's immune system than transplanted cells from donor tissue.

"This is the big idea in the long run. We hope to be able to do a biopsy on a patient, make dopamine cells, for example, and then transplant them as a treatment for Parkinson's disease," says Malin Parmar, who is now continuing the research to develop more types of brain cells using the new technique.

/Science Daily/

URL: http://www.today.az/news/interesting/88167.html

Print version

Print version

Views: 1682

Connect with us. Get latest news and updates.

See Also

- 19 February 2025 [22:20]

Visa and Mastercard can return to Russia, but with restrictions - 05 February 2025 [19:41]

Japan plans to negotiate with Trump to increase LNG imports from United States - 23 January 2025 [23:20]

Dubai once again named cleanest city in the world - 06 December 2024 [22:20]

Are scented candles harmful to health? - 23 November 2024 [14:11]

Magnitude 4.5 earthquake hits Azerbaijan's Lachin - 20 November 2024 [23:30]

Launch vehicle with prototype of Starship made its sixth test flight - 27 October 2024 [09:00]

Fuel prices expected to rise in Sweden - 24 October 2024 [19:14]

Turkiye strikes terror targets in Iraq and Syria - 23 October 2024 [23:46]

Kazakhstan supplied almost entire volume of oil planned for 2024 to Germany in 9 months - 23 October 2024 [22:17]

Taiwan reported passage of Chinese Navy aircraft carrier near island

Most Popular

Separatists & Pashinyan - the farce continues

Separatists & Pashinyan - the farce continues

4SIM signs MoUs with Chinese institutions to boost cooperation in green and industrial technologies

4SIM signs MoUs with Chinese institutions to boost cooperation in green and industrial technologies

Antalya Diplomacy Forum becomes center of global dialogue

Antalya Diplomacy Forum becomes center of global dialogue

A fat, nosy and bald hint that Armenia will remove claims against Azerbaijan from the Constitution

A fat, nosy and bald hint that Armenia will remove claims against Azerbaijan from the Constitution

Collapse of "macaronism": Resignation of the "grey cardinal" of France may cause a chain reaction

Collapse of "macaronism": Resignation of the "grey cardinal" of France may cause a chain reaction

Paris hosts debut of Azerbaijan’s first AI art “Shusha”

Paris hosts debut of Azerbaijan’s first AI art “Shusha”

Foreign diplomats tour liberated cities of Khankendi and Shusha

Foreign diplomats tour liberated cities of Khankendi and Shusha